![]()

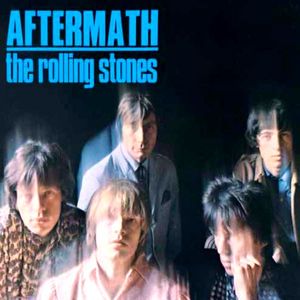

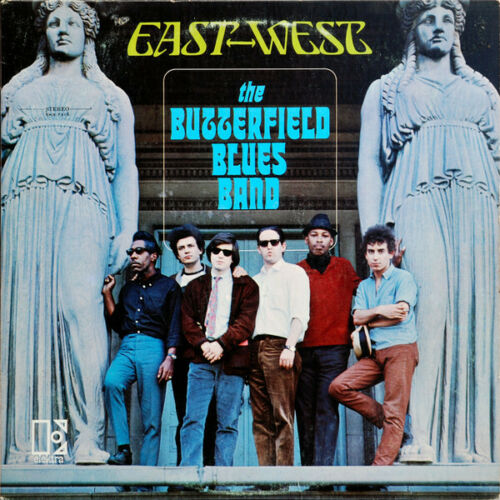

Over the years there have been many arguments concerning which year produced the best rock album. While this is most probably arrived at via a subjective view point, there is a serious case to be made for the year 1966; a year which produced such classics as Dylan's Blonde On Blonde, The Beach Boys aka Brian Wilson's Pet Sounds, the Beatles' Revolver, Aftermath by the Rolling Stones and East-West by The Butterfield Blues Band. In a way, 1966 reflected the changing structure of rock & roll while also defining the future direction of rock music. The albums I just mentioned set the bar for taking a visceral approach when it came to creating albums that would mean something and endure the test of time. There was a palpable sense of change encased in the music of 1966. It was the year that rock & roll transformed itself into rock music.

"What’s the most innovative year ever for rock ’n’ roll? Fans, critics and academics have any number of watershed years they can point to in the more than six decades of post-World War II popular music broadly defined as rock. There’s 1954, the year Bill Haley & His Comets’ Rock Around the Clock signaled the flashpoint of rock ’n’ roll, and Elvis Presley first stepped up to a microphone at Sam Phillips’ Sun Studio in Memphis, Tenn. Or 1964, the year Beatlemania exploded around the world and the launch of the British Invasion. Don’t discredit 1967, with the Summer of Love, the blossoming of flower power and psychedelic music. Some stand by 1977, which saw the arrival of that young, loud and snotty music called punk rock...But 50 years down the line, a case can be made that 1966 may have been the single most creatively expansive year of all." (Los Angeles Times)

"It was a time of enormous ambition and serious engagement. Music was no longer commenting on life but had become indivisible from life. It had become the focus not just of youth consumerism but a way of seeing the prism through which the world was interpreted. 1966 began in pop and ended with rock. Along with the increased ambition to be heard in the music, it was a year of rapid change and development in the various liberation movements - not just civil rights - the engine of dissent in the mid-sixties - but women's rights and the emerging homophile movement...Everyone thinks they know a out the sixties. It was a golden pop age; it was the moment when everything started going downhill. It was the start of an alternative society; it was only a couple of hundred people in London while real life - whatever that is - went on elsewhere...The premise throughout this time is that music did reflect the world during 1966; that it was connected to events outside the pop culture bubble and was understood to do so by many of its listeners; that there was something more than image and sales at stake. It was a year when audacious ideas and experiments were at a premium in the mass market and in youth culture, with a corresponding backlash from those for whom the rate of change was too quick. The resulting tension was terrific...1966 was a year of noise and tumult, of brightly colored patterns clashing with black and white politics, of furious forward motion and an outraged, awakening reaction. There was a sense that anything was possible to those who dared, a willingness to strive towards the seemingly unattainable. There remains an overwhelming urgency that marks the music and movies of that year, counter-balanced by traces of loss, disconnection and deep melancholy. But underneath all the sound an fury - and the moments of regret - lies a profound silence. This is not the silence of peace, of solitude, of sought withdrawl - or even of meditation...It's not a silence that exists within itself; it is a rupture, a prelude to something that if barely conceivable. This silence is an artificially created vacuum - a few instants of bone-shaking terror - that turns the world inside out....1966 was the sixties peak, the year when the decade exploded." (Jon Savage, 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded)

"Most appreciations of '66 zero in on a handful of Acknowledged Masterpieces by Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones. Which makes sense. They'd all belong on any list of albums that shook the world. However, it wasn't only that those few LP's were so towering.

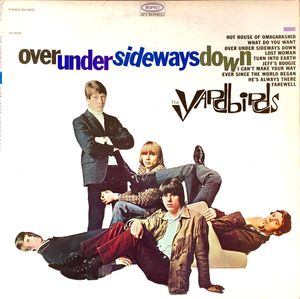

In 1966, the 8th or 9th best British or American band (Them, let's say, or the Standells), could find room near the top of any reasonable person's best-of list without fear of ridicule. It was a freakish, unprecedented barrage: if your year-end Top 10 scribbled on 12/31/66 included those Acknowledged Masterpieces plus albums by Otis Redding, The Kinks, The Lovin' Spoonful, John Mayall's Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton, The Mothers of Invention, The Yardbirds, Tim Hardin, The Animals, Donovan, The Blues Project, and the Young Rascals. That's just for starters...

Consider this: in 1966, 27 different singles made #1 on the Billboard chart, more than in any other year from the beginning of the rock and roll era (1955) to the end of the 1960's. You couldn't keep up with the comings and goings of songs scampering up and sliding down the charts, but that side of the pop sphere was always about the hit single.

What was changing in '66 was the rise of the rock album; it was as though the previous year's Rubber Soul and Highway 61 Revisited gave everyone permission to creatively stretch out across two (or in the cases of Dylan and Zappa, four) album sides, sometimes at insane length (e.g., The Seeds' Up in Her Room), sometimes brilliantly (the Paul Butterfield Blues Band's East-West).

1966 was The Spot. The crossroads of AM and FM, mono and stereo, 45 and 33⅓, mod and hippie, the Beach Boys on the West Coast, the Four Seasons on the East Coast. It wasn't a great year because 'Pet Sounds' and 'Blonde on Blonde' came out, but because 'Pet Sounds' and 'Blonde on Blonde' were a part of something bigger.

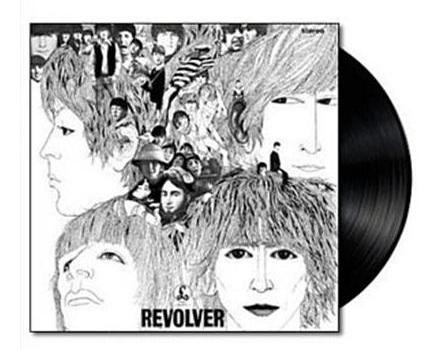

1966 was David Bailey shooting Jean Shrimpton for Vogue and the Stones for 'Aftermath'; Jerry Schatzberg's fuzzed-up fold-out on 'Blonde on Blonde'; Klaus Voormann's black-and-white collage on 'Revolver'; Jean-Marie Perier's shots of Francoise Hardy and his photo of Marianne Faithfull in the high grass on the cover of 'Faithfull Forever'; Guy Webster's sunlight-streaked shots of the Mamas and the Papas; the pop art on The Who's A Quick One." (Music Aficionado, Mitchell Cohen, Why 1966 Was The Best Year for Music Ever)

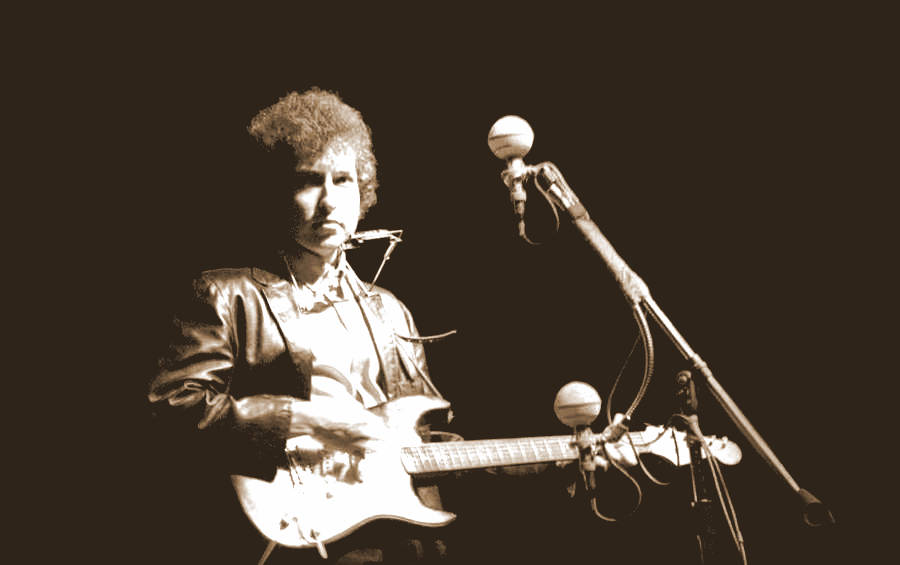

In 1966, Bob Dylan released the very first double album in rock & roll and it was called Blonde On Blonde.

"it represented a tipping point in popular music, redefining the possibilities of rock and roll and more. It changed the way artists approached the genre, as well as the way fans listened to it. With his fusion of poetry and rock in its broadest sense, Dylan liberated other artists, giving them license to express their inner poet through their music. The record also accelerated the shift of focus in popular music from singles to albums, and in the process, elevated the long-playing record as an art form...Blonde on Blonde unquestionably had an impact on singer-songwriters and that album was one of the pinnacles of those times." (That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound, Daryl Sanders, Chicago Review Press)

"Blonde On Blonde remains Dylan’s most eclectic, mercurial and indecipherable album; even the famous cover portrait is out of focus. The record cannot be seen out of context: it completed the mid-1960s trilogy, following Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited. Five months before recording began, Dylan had made arguably the most significant step in his career, and perhaps in all rock music, when on Sunday 25 July 1965, he played the Newport folk festival with a band that included Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield and proceeded to rip the night apart with searing electric accounts of Maggie’s Farm, Like a Rolling Stone and It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry. He was booed, (as he would be when he took the sound to Britain in 1966) although Joe Boyd, who mixed that sound at Newport, recalls how 'more people liked it than didn’t.'.

After an initial recording in which One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later) was laid down in New York in January 1966, the rest of the album was laid down in Nashville over two sessions from 14-17 February and 7-10 March – 13 songs in six days, all on four tracks, not eight as has been suggested – ergo, more than one instrument on each track.

From his touring band The Hawks (later The Band), Dylan brought Robbie Robertson on lead guitar and Al Kooper on shimmering Hammond, and the most accomplished country session men in town, including Kenny Buttrey on drums, Wayne Moss and Joe South on guitars, and bassists Charlie McCoy and Henry Strzelecki.

Of the first Nashville session, Dylan has said: 'The musicians played cards, I wrote out a song, we’d do it, they’d go back to their game and I’d write out another song.' Actually, the band was often woken up and summoned to the studio in the middle of the night. The musicians were arranged in a circle, so as to feed off one another. And most of the songs from those first sessions were indeed completed by a first or second take: Fourth Time Around, Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat and the record’s two haunting and haunted masterpieces: Visions of Johanna and Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.

Drummer Kenny Buttrey’s recollections of recording Sad-Eyed Lady, in Clinton Heylin’s book Behind the Shades, are a revelation: Dylan said, he recounts, '‘We’ll do a verse and chorus and I’ll play my harmonica thing … and we’ll see how it goes from there’ … We prepared ourselves ... for a basic two- to three-minute record.' However, 'a second chorus starts building and building like crazy, and everybody’s just peaking it up, ’cause we thought, man, this is it… After about five, six minutes of this stuff, everyone starts looking at each other, we’d built to the peak of our limit.' Yet they continued, at that peak, for 11 minutes, 22 seconds.

Blonde on Blonde denies resolution, resorting instead to the absurd. The absurd in the album I later found in Samuel Beckett, and his hollow laugh, which one learns, and to which one surrenders, later in life. Or in Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues, with their despairing irony and wit." (The Guardian, 2016)

1966 Playboy Magazine Bob Dylan Interview

Legendary photographer Barry Feinstein (who previously shot the cover of Dylan’s album The Times They Are a-Changin’ in 1964) accompanied Dylan on the UK leg of the tour at the musician’s behest to document the goings-on, both onstage and off. The 1966 tour was also filmed by director D. A. Pennebaker whose footage was edited by Dylan and Howard Alk to produce a little-seen film, Eat the Document, an anarchic account of the tour. Drummer Mickey Jones also filmed the tour with an 8mm home movie camera.

During many of the concerts, members of the audience, refusing to accept Dylan's new electrified music, booed Dylan and his band.

Many of the 1966 tour concerts were audio recorded by Columbia Records. These recordings eventually produced two official albums, the so-called Royal Albert Hall concert and in 2016, The Real Royal Albert Hall Concert, as well as The 1966 Live Recordings, a 36 CD box set of every recorded concert from the 1966 tour. There are also many unofficial bootleg recordings of the tour.

Dylan's 1966 Tour ended with his motorcycle accident late on Friday afternoon, July 29, 1966.

"Widely considered a Brian Wilson solo project, this seems harsh on Tony Asher’s lyrics (elegantly distilling Wilson’s fractured state of mind), and the band members’ iridescent harmonies. An admirer of Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, Wilson also had a friendly rivalry with The Beatles. Just as Wilson loved Rubber Soul, John Lennon hailed Pet Sounds as the greatest album ever; McCartney said that, without it, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band couldn’t have happened. While Pet Sounds was feted in Britain, it barely scraped into the top 10 of the US Billboard 100...making Pet Sounds half a century ago, Wilson reinvented the album as the in-depth illumination of an artist’s soul, kicking open a creative fire-door, liberating the album to exist as a self-contained art form on a par with literature, theater, art, cinema, dance; anything the artist desired." (The Guardian, Was 1966 Pop's Greatest Year?)

"In the summer of 1966 there were some fans who were confused by The Beach Boys’ 11th studio album – where were the striped shirts and the surfboards? In the intervening five decades, however, Pet Sounds has been acknowledged as a masterpiece, a record that has topped countless polls of the greatest albums ever made, and is revered by musicians and fans alike as the pinnacle of Brian Wilson’s songwriting, production and all-round creative genius. Brian began seriously working on his masterpiece on Tuesday, 18 January 1966, at Western Recorders, and continued for 27 sessions spread over three months at four separate Los Angeles studios. This was an unprecedented amount of studio hours to be devoted to one album, but Brian was in pursuit of perfection. Just take a listen to any of the tracking sessions released on the various reissues of Pet Sounds: Brian was totally focused and demanded nothing less from everyone who worked on the project." (Udiscovermusic.com 2018)

"Pet Sounds, though, was a sustained act of complex creation, one part work of orchestral ambition, one part proto-concept album. A nervous breakdown on a flight between LA and Houston in December 1964 had prompted Brian Wilson to refocus his energies from touring and promotion to the more enjoyable pursuits of songwriting and the boundless potential of the recording studio. He had been further liberated by his introduction to marijuana and hallucinogenics the following year. Now, with The Beatles’ Rubber Soul ringing in his ears and his competitive streak risen, he set out to make what he promised his wife Marilyn would be 'the greatest rock album ever made'. To turn the pocket symphonies in his head into gorgeous reality, he made two crucial moves. Firstly, he entrusted the task of translating his ideas about the loss of innocence and the imponderability of existence to advertising copywriter-turned-lyricist Tony Asher. Secondly, he enlisted the help of ace session musicians The Wrecking Crew, including guitarist Glen Campbell and bassist Carol Kaye, veterans of Phil Spector’s Wall Of Sound, with the 23-year-old Wilson orchestrating the sessions himself. The resultant songs – Wouldn’t It Be Nice, Don’t Talk (Put Your Head On My Shoulder), I’m Waiting For The Day, God Only Knows, I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times, Caroline, No – were perfect miniatures of hymnal wonder, which expressed with devotional clarity the anxieties and longings of an adolescent poised on the cusp of agonizing maturity...But Wilson wasn’t done. Pet Sounds may have stalled at No.10 in the US after its release in May 1966, but any disappointment at its commercial performance was allayed by the arrival of a new single, Good Vibrations, in October. With its modal shifts and multi-sectional mosaic of sound fragments pieced together by Wilson over eight months in multiple studios, it set new standards with regard to what rock music could sound like and do, and blazed a trail for others to follow. It was the epic, euphoric anthesis of Pet Sounds’ glorious melancholia. But how to describe it? The first psychedelic single? Acid bubblegum? Something else? In his own roundabout way, Brian Wilson answered the question himself when asked whether Good Vibrations was a pioneering example of progressive rock? 'Yes,' he replied simply, 'it was.'” (loudersound.com 2018)

In the fall of 1966, Brian Wilson was conducting sessions for a new album called SMILE; a project that was empowered by Wilson's ambitions as a producer for The Beach Boys.

"The material for the new album abounded in short feels, beautiful fragments that were in varying stages of completion but were not yet assembled, as was intended into part of a larger whole. It was only Wilson who knew the design, and there were signs that the complicated patchwork was beginning to unravel....Wilson was completely in control of the studio, teaching each musician their part, which he already had in his head." (Jon Savage, 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded)

When work began on a track called 'Fire' that things began to go awry. "They began the take: A gigantic fire howled out of the massive studio speakers in a pounding crush of pictorial music that summoned up visions of roaring, windstorm flames, falling timbers, mournful sirens and sweating firemen, building into a peak and crackling off into fading embers as a single drum turned into a collapsing wall and the fire-engine cellos dissolved and disappeared. 'Fire' is indeed one of the most frightening pieces of music ever to come out of Los Angeles...Nothing could have been more different to the tenderness of Pet Sounds." (Jon Savage, 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded)

"After a hiatus following their last tour, the Beatles had decided that live dates were definitely not on the agenda. As they recounted various horror stories from their summer tour, Geoff Emerick, the EMI studio engineer, noted that 'beneath the usual banter, the four Beatles were considerably more subdued, more on their guard that they had ever been before. Clearly, the events of the past few months had taken a toll on them; they seemed almost robbed of their youth. No longer were they the four cuddly mop tops; now they looked and acted like seasoned musicians, weary veterans of the road." (Jon Savage, The Year The Decade Exploded)

"As they devoted more time to the studio, the Beatles' individual voices and confidence continued to grow, resulting in the sonic landmark Revolver. Like any band, the Beatles' recording career was often altered, even pushed forward, as much by external factors as their own creative impulses. The group's competitive drive had them, at times, working to match or best Bob Dylan or Brian Wilson; their drug use greatly colored the musical outlook of John Lennon and George Harrison in particular...The most important of these external shifts in the Beatles narrative, however, was a series of changes that allowed them to morph into a studio band. The chain of events that ushered in the band's changing approach to studio music began before Rubber Soul, but the results didn't come into full fruition until Revolver, a 35-minute LP that took 300 hours of studio time to create-- roughly three times the amount allotted to Rubber Soul, and an astronomical amount for a record in 1966...This new approach not only greatly altered their work environment, but drove the Beatles to value the flexibility of emerging technology. They also cashed in some of their commercial capital to abandon the mentally and physically sapping practice of touring-- and the glad-handing and public relations requirements that went with it. Exceptionalism became the watchword for the band, and it responded by using its freedom to push forward its art and, by extension, the whole of pop music. Musically, then, the Beatles began to craft dense, experimental works; lyrically, they matched that ambition, maturing pop from the stuff of teen dreams to a more serious pursuit that actively reflected and shaped the times in which its creators lived." (pitchfork.com, Scott Plagenhoef, The Beatles Revolver)

"Producer George Martin, who by all accounts, was the closest thing there was to a fifth Beatle, helped guide the group’s innovative sound— from the double-string quartet on Eleanor Rigby to the French horn obligato on For No One...t was also thanks to 20-year-old engineer Geoff Emerick, who was promoted to replace veteran Norman Smith. Emerick is most notable for his work on the first track recording for Revolver, Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows.” By recording his voice through a Leslie speaker, it gave it the faraway sound the song is known for, which was something that had never been done before. It was ideas like this, along with the microphone placement for McCartney’s bass and Starr’s drums, that paved the way for the way studio recordings were done after Revolver...But it wasn’t just the studio effects and instruments that made Revolver stand out from the rest of the Beatles catalog. It was the songwriting...All four Beatles were arguably at their artistic peak in 1966. But during the Revolver sessions, the group also showed signs of crumbling as each member started pursuing their own creative paths...as 1966 neared its end, the group began work on Strawberry Fields Forever, a song written by Lennon that would guide the band’s musical direction in the coming year." (Cuepoint website, Charles J. Moss, How the Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ Gave Brian Wilson a Nervous Breakdown)

"There's a moment in almost every legendary artist's career that marks the period in which they transcend the merely good and become truly great. Aftermath is the Rolling Stones' moment. By the time they put out Aftermath on April 15, 1966, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were writing all of the band's songs. The songs are bigger and bolder. They take more risks, wandering outside of the blues and R&B parameters that steadied the band during its first three years. And for the first time, a Rolling Stones album plays like one – an LP crafted to come together as a total listening experience. The album was made during a handful of sessions in Hollywood in early December 1965 and early March 1966. It was the group's first LP to be recorded entirely in the U.S., and the first in which Brian Jones played around with a variety of instruments not exactly known for their use in rock music: dulcimer, marimba, sitar and koto, a traditional Japanese stringed instrument, among them. Like other notable albums from 1966 Aftermath was a pivotal moment in both the artist's career as well as an advancement for rock 'n' roll in general. The Stones' record arrived before all of them, signaling a turning point in the future direction of popular music." (Ultimate Classic Rock site, Michael Gallucci, How the Rolling Stones Took a Big Leap On Aftermath)

"Although it was their fourth album released in Britain and their sixth album released in America, Aftermath was really the second “true” album by The Rolling Stones, following 1965’s Out Of Our Heads. This one, like that previous one, was released in two distinct versions in the UK and in the USA, a common practice for the day (this review will look at the “greater” album, considering all the tracks included on either version of Aftermath). The UK hit single “Paint It Black” was added to the American version, replacing four songs that were included on the UK version. With Out Of Our Heads, the band reached the peak of their mid-sixties (then cutting-edge) mixture of Chicago-style blues and pop-rock. Aftermath builds on this while it progresses the band more towards their distinct sound and image as “rock and roll’s bad boys”. It is also the first Stones album to include all original material, written by the tandem of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Although not himself a songwriter, multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones was the driving force behind some of the unique and distinct sonic quality of the album. Jones incorporated wider musical influences, such as psychedelia and folk, and widely expanded the use of instrumentation, with songs on Aftermath including touches of dulcimer, sitar, marimba, and various keyboards." (Classic Rock Review)

Another album that belongs in the pantheon of all the albums listed above is East-West by the Butterfield Blues Band. "That the first psychedelic album might have come from a blues band was one thing. That one of the most influential blues albums of all time might have come from the same group, well, that was another. That both things were wrapped up inside the Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s East-West, however, is undeniable. Butterfield was joined on his sophomore record by guitarist Elvin Bishop, bassist Jerome Arnold, keyboardist Mark Naftalin, drummer Billy Davenport and lead guitarist Mike Bloomfield, who, like Butterfield, was at his peak. Each member brought his own interests into an increasingly collaborative structure. 'Pre-East-West, I was listening to a lot of Coltrane, a lot of Ravi Shankar and guys that played modal music,' Bloomfield said in a WBEZ interview, 'And the idea wasn’t to see how far you could go harmonically, but to see how far you could go melodically or modally. And that’s what I was doing in East-West, and I think that’s why a lot of guitar players liked it.' East-West arrived in August 1966 as a swift kick to the doors of convention, in particular with its Eastern influences and long-form jams. Both rock and blues were absorbed in the aftershocks for years. Its impact on Santana and the Grateful Dead, for starters, can't be overstated." (Ultimate Classic Rock website: Nick Deriso, 50 Years ago: Paul Butterfield Blues Band Re-Writes Rock's Rule Book with East-West)

Like the band's eponymous record debut, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, this album features traditional blues covers and the guitar work of Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop. Unlike the debut album, Bishop also contributed guitar solos; drummer Sam Lay had left the band due to illness and was replaced by the more jazz-oriented Billy Davenport. The social complexion of the band changed as well; ruled by Butterfield in the beginning, it evolved into more of a democracy both in terms of financial reward and input into repertoire.

One result was the inclusion of two all-instrumental extended jams at the instigation of Bloomfield following the group's successful appearance at The Fillmore in San Francisco during March alongside Jefferson Airplane.[4] Both reflected his love of jazz, as the blue note-laden "Work Song" featuring harmonica by Butterfield had become a hard bop standard, and the title track "East-West" used elements of modal jazz as introduced by Miles Davis on his ground-breaking Kind of Blue album. Bloomfield had become enamored of work by John Coltrane in that area, especially his incorporation of ideas from Indian raga music. The album also included Michael Nesmith's song "Mary, Mary," which Nesmith would soon record with his band The Monkees - although original pressings of East-West did not include a songwriter's credit for this track.

In an interview, keyboardist Mark Naftalin notes that the song East-West was inspired by an all-night LSD trip that primary songwriter Mike Bloomfield experienced in the fall of 1965, during which the late guitarist said 'he'd had a revelation into the workings of Indian music.'

Naftalin went on to explain that ;The song was based, like Indian music, on a drone. In Western musical terms, it 'stayed on the one'. The song was tethered to a four-beat bass pattern and structured as a series of sections, each with a different mood, mode and color, always underscored by the drummer, who contributed not only the rhythmic feel but much in the way of tonal shading, using mallets as well as sticks on the various drums and the different regions of the cymbals. In addition to playing beautiful solos, Paul [Butterfield] played important, unifying things [on harmonica] in the background - chords, melodies, counterpoints, counter-rhythms. This was a group improvisation. In its fullest form it lasted over an hour.' The album is also credited with spawning the harder acid rock sound. The track East-West, with its early use of the extended rock solo, has been described as laying 'the roots of psychedelic acid rock' and featuring 'much of acid-rock's eventual DNA.

Crawdaddy! First Issue 1966

Paul Williams (founder of Crawdaddy Magazine)

Paul Williams (founder of Crawdaddy Magazine)

Crawdaddy Magazine, started by the late great Paul Williams, was the first credible magazine dedicated to rock music. "A year and a half before Jann Wenner founded Rolling Stone, a teenager named Paul Williams started Crawdaddy! magazine. Launched in January 1966 by the precocious 17-year-old Swarthmore college student, Crawdaddy! was the first American music magazine to take "rock" music seriously. This was the era of Teen Beat and Tiger Beat,when pop stars were more likely to be asked about their favorite color rather than what inspired their creativity. Writer/editor Paul Williams, who died on Wednesday at the age of 64, changed all that by asking burgeoning legends like Brian Wilson and David Crosby what they were really thinking about. Amazingly, Williams (still totally unknown at that point) was able to invite himself into recording studios for impromptu and candid conversations with The Beach Boys and Crosby, Stills & Nash during an era that predated the personal manager, the publicist and the bodyguard. Originally, Crawdaddy! was solely written, edited and published by Williams in his dorm room, but within 18 months it grew into a real venture with an office and staff in New York City which provided music journalists Peter Guralnick, Jon Landau and Richard Meltzer with their first writing outlet." (NPR, Remembering Paul Wiliams)

"Of course, there’d be no 1966 rock – or 2016 rock, for that matter – without the blues. We mentioned the Stones, but this was the year when many bands stopped merely imitating Howlin’ Wolf and Skip James (those two legends both found new audiences in Britain), and discovered ways to transcend the blues. On The Spiders’ Don’t Blow Your Mind, teenage Alice Cooper threw the 12-bar form down a deep well, then yowled up from the bottom in the midst of a fuzz-bass thunderstorm. On Wild Thing, The Troggs lived up to their name by banging a savage caveman sensibility into the catchiest I-IV-V workout ever.

Then there was Shapes Of Things. Next to Tomorrow Never Knows, it may be the most forward-looking song of the year. Pro-environment and Anti-war lyrics, a bass riff borrowed from a Dave Brubeck jazz record, a martial beat, abrupt tempo shifts, all capped off with Jeff Beck’s free-form feedback solo.

If there’s one word that sums up 1966, it’s ‘free’. Jimi Hendrix said: 'We don’t want to be classed in any category. If it must have a tag, I’d like it to be called Free Feeling. It’s a mixture of rock, freak-out, blues and rave music.' Frank Zappa said: 'We play the new free music – music as absolutely free, unencumbered by American cultural suppression. We are systematically trying to do away with the creative roadblocks that our helpful educational system has installed to make sure nothing creative leaks through to mass audiences.' And John Sebastian said: 'As the various categories of popular music break down and mulch, there are what the clerical onlooker calls new sounds. They are more accurately old new sounds, new old sounds, a free exchange.'” (Classic Rock www.loudersound.com)

Here's some albums that also played a big part

in what I was listening to back in 1966

A Quick One - The Who

In '66 and in '67 I was hypnotized by The Who. I always considered a classic singles band but A Quick One really found them moving into different territory all together...most notably with the presence of the title track, Pete Townshend's first effort at writing a mini-opera. For me, I found Pete Townshend's power pop numbers such as So Sad About Us and Run Run Run to be simply magnificent.

"As an albums band, the Who didn't peak until the early Seventies. Their mid-Sixties offerings, A Quick One and The Who Sell Out, are both charming examples of a band shaking off their Mod image. Before the band began recording A Quick One, their co-manager, Chris Stamp, negotiated a deal providing each member with an advance of £500, on condition they all contributed songs to the album (in 1966 this was a small fortune for any 21-year-old)...this variety showcase includes Keith Moon's humorous Cobwebs and Strange, a wonky marching tune complete with orchestral cymbals, trumpets and sousaphone...Roger Daltrey pays tribute to Buddy Holly on the forgettable See My Way and John Entwistle throws in a couple of songs about whisky and spiders. His creepy ditty Boris the Spider remained an audience favorite for years.

The highlight on this album, however, is Pete Townshend's sprawling title track, originally the albums closing number. Its almost ten minutes long: extraordinary, in the days of three-minute throwaways. Not even the Beatles had recorded anything as long. The reason for this is less artistic bravado than plain pragmatism.

After the band had cut the available tracks for the album, Townshend, always the primary composer within the group, was requested to fill the remaining minutes to push the running time over half an hour. A Quick One While He's Away is Townshend's first attempt at a rock opera, perhaps the first in pop music. It's a suite of six episodes, comprising a simple tale of an unfaithful wife who has a quick leg-over with a lover called Ivor and is happily absolved by her husband. Each is a self-contained song, the whole spliced together in much the same way as Abbey Road's long medley would be, three years later. This was an audacious concept in 1966 and, although the track now sounds clunky and awkward, its fascinating to hear Townshend setting out on the path that would eventually lead to Tommy and Quadrophenia." (BBC)

Face To Face - The Kinks

I've always considered Ray Davies to be an all-time great songwriter. This particular album was a great leap in quality for The Kinks. Over the years it has garnered rave reviews from many rock journalists. I find Face To Face to be on par with The Beatles Revolver and while that may anger many Beatle fanatics, it's true.

"The Kink Kontroversy was a considerable leap forward in terms of quality, but it pales next to Face to Face, one of the finest collections of pop songs released during the '60s. Conceived as a loose concept album, Face to Face sees Ray Davies' fascination with English class and social structures flourish, as he creates a number of vivid character portraits. Davies' growth as a lyricist coincided with the Kinks' musical growth.

Face to Face is filled with wonderful moments, whether it's the mocking Hawaiian guitars of the rocker Holiday in Waikiki, the droning Eastern touches of Fancy, the music hall shuffle of Dandy, or the lazily rolling Sunny Afternoon. And that only scratches the surface of the riches of Face to Face, which offers other classics like Rosy Won't You Please Come Home, Party Line, Too Much on My Mind, Rainy Day in June, and Most Exclusive Residence for Sale, making the record one of the most distinctive and accomplished albums of its time." (All Music)

The Kinks Face to Face wasn’t exactly a concept album, but it did have a loosely fitting theme of observational songs about people, mostly in turmoil. Ray enjoyed observing and commenting on the upper class, especially when he could tear down the façade of happiness to expose the bleak side, as on Most Exclusive Residence For Sale. Dandy, a hit for Herman’s Hermits, gently mocks clothes horse superficiality and Session Man goes after hired musical guns, though the album uses Nicky Hopkins on keyboards, who added plenty to the proceedings.

There’s not a weak tune on the album and all of them hold up well...including the humorous ones like Party Line and the almost throw away Holiday in Waikiki, but the real stand-outs are the dark songs Too Much On My Mind and especially the drone-like Fancy, which might be the album’s deepest cut.

1966 was also a year in which music consumers were overwhelmed by the volume of new music gizmos that flooded the marketplace. The history of music is inseparable from the history of technology. From the first primitive percussion instruments, catgut strings, and animal horns, to Thomas Edison’s phonograph and the jukebox, how we listen and create has evolved with the tools of the times. By the 1960's, the technological conditions were ripe for the birth of popular music as it’s often idealized today, with AM and FM radio going mainstream, vinyl records supplanting the earlier shellac format, and multi-track recording developments clearing the way for late-’60;s studio experimentation.

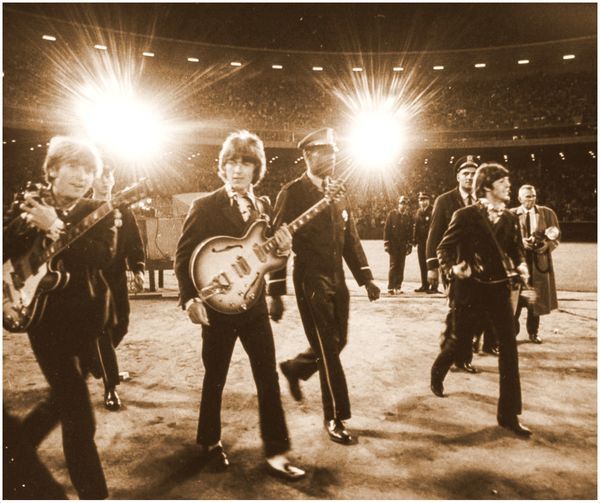

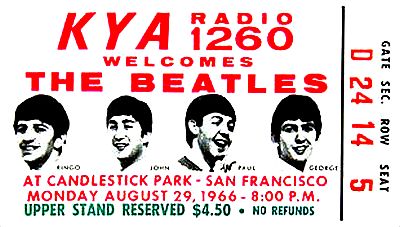

One of the most significant musical events of 1966 was the fact that The Beatles played their last live show on Monday August 29th at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, California. The Park's capacity was 42,500, but only 25,000 tickets were sold, leaving large sections of unsold seats (this was most probably due to John Lennon's remark that "The Beatles are bigger than Jesus" which led to some folks burning all of their Beatles albums). Fans paid between $4.50 and $6.50 for tickets, and The Beatles' fee was around $90,000. This arrangement, coupled with low ticket sales and other unexpected expenses resulted in a financial loss for Tempo Productions.

The 1960's remain in memory as a golden age of pop culture, with 1966 enshrined...as the year of swinging London. It was the year of the singles that are regularly collected on those TV advertised compilations: Sunny Afternoon; Reach Out I’ll Be There; Good Vibrations; Summer in the City – mass pop art so imperishable that it cannot be dimmed by cheap nostalgia and endless repetition.

1966 was a year of turmoil. It began in pop and ended in rock...It was also the year that the torch passed from England to America, from London to Los Angeles, which became the central pop location, thanks to the Mamas and the Papas, the Beach Boys, and the Monkees – ersatz Beatles who bloomed just as the originals left the stage. California had its own youthtopias, reasonably autonomous zones where the young could congregate and try out new ways of living: the Haight Ashbury in San Francisco, the Sunset Strip in Hollywood.

Pop’s Herculean acceleration resulted in many casualties: during 1966, the Beatles, Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones all crashed out from the pace, but not before they had provocatively expressed their dissatisfaction – Dylan with his polarizing electric show segments, the Beatles with their notorious Butcher LP sleeve (pulped by their American record company, Capitol, at a cost of $200,000), the Rolling Stones with the drag video for Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?...By 1966, many strands of art, music, and entertainment were all coming to the same point by different means: the total focus on the instant that is the hallmark of many eastern religions; the happening; the drug experience; the ecstasy of dancing...Pop music was the new Olympus. Lou Reed recognized it as the arena for his generation: 'The music is the only live, living thing.'

"The most obvious example of how rock music had changed is when the Beach Boys’ recorded the album Good Vibrations which was recorded in sessions that spanned 60 hours over seven months; it was technological yet emotional, sensual and spiritual – designed as a moment of fusion that would reset pop culture’s polarity to positive. What was thrilling about 1966 was the way in which things were not business as usual, a feeling that can still be heard in the records of the year: music was connected to events outside the pop culture bubble and was understood to do so by many of its listeners. It was a year when audacious ideas and experiments were at a premium in the mass market and in youth culture, with a corresponding reaction from those for whom the rate of change was too quick. The 60's peaked in 1966...The songs from that time still enchant successive generations, but they were also a response to their place and time." (The Guardian, 1966: The Year The Youth Culture Exploded)

The Doors Live @ The London Fog cub circa 1966

The Doors Live @ The London Fog cub circa 1966

A few months after the Doors formed, they earned their first steady gig in 1966 at the London Fog, a nightclub on the Sunset Strip. The band earned $5 per night, playing for relatively few patrons; new to performing, Jim Morrison frequently sang with his back toward the small crowd. Ray Manzarek remarked that the London Fog was where the group 'became a collective entity, this unit of oneness'.

Although they covered some blues standards, most of the time the Doors honed their signature sound and material that later appeared on their first two albums – The Doors and Strange Days – also adding improvised solos to extend the set times.

In 1966, popular music saw a split in music preferences; the best example of this was that older teens preferred The Beatles while the younger brothers and sisters of those older teenagers idolized The Monkees. In a way, this split was able to let the younger kids maintain the precocious fandom as reflected in Beatlemania and the older kids would invest themselves in a more young adult-oriented sounds.

"By late 1966, simple consumerism would not be enough for the radical or even thoughtful young. Pop culture was thus caught in a cleft stick, propagating ideas and attitudes critical of materialist society at the same time as it was an integral part of that society in its rawest economic form. Together with the beginnings of youth's self-identification not just as a marketing class but as a growing social cohort, politics of all types would increasingly dominate the agenda...The age of innocence -- if not willed ignorance -- was over." (Jon Savage, 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded)

“The rock's easy, but the roll is another thing...”

- Keith Richards Interview November 1966

In 1966, Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic, a ritualistic multi-media show which was supported by Andy Warhol and featured The Velvet Underground and Nico, had a major impact on the the youth culture and its music.

Between the events staged by Warhol and his crew along with the burgeoning scene that was developing in San Francisco, the year ushered in a sense of communal identity wherein the distance between the performers and the audience began to change.

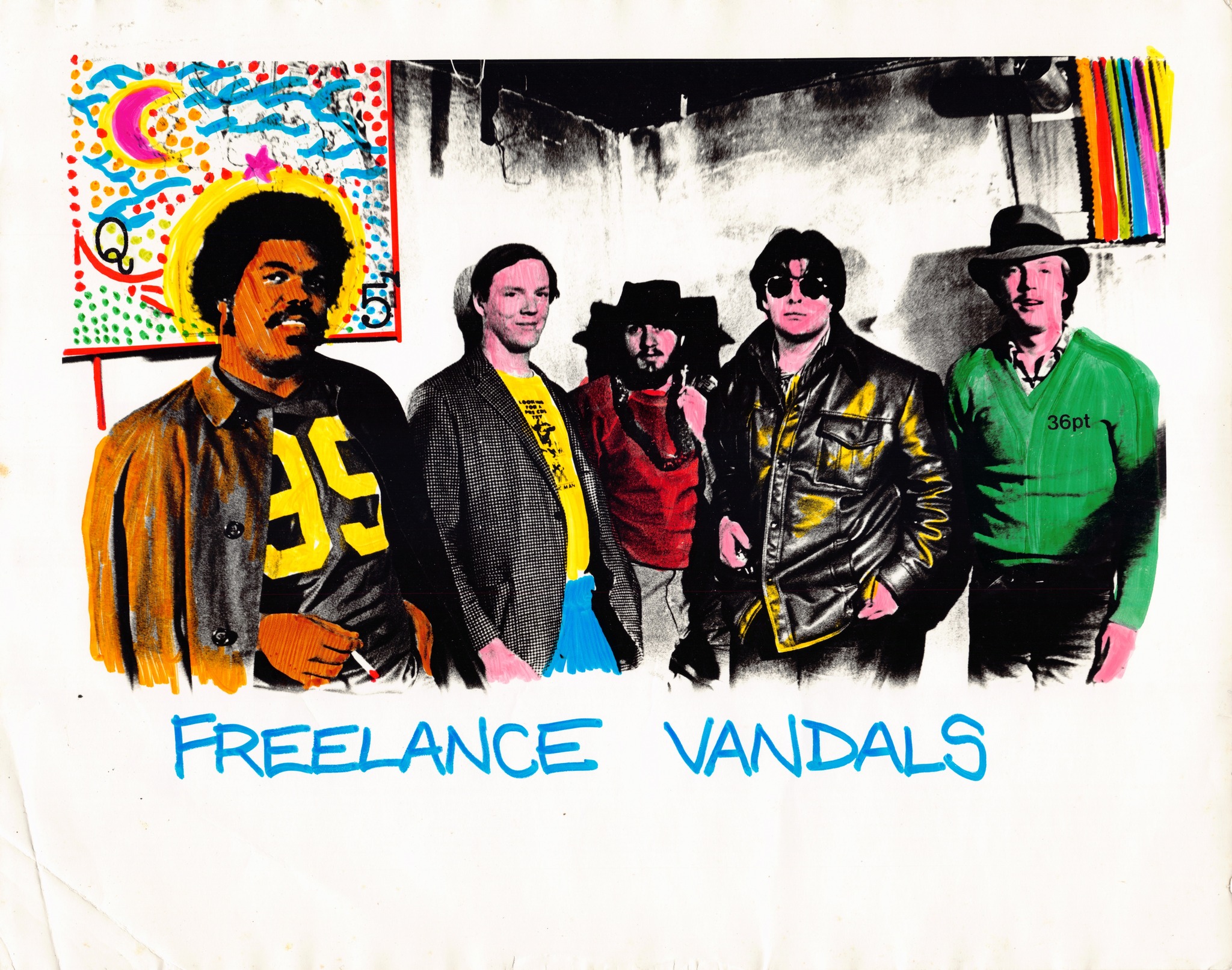

FREELANCE VANDALS 1979 WBAB SHOW @ THE SILVER DOLLAR SALOON

AVAILABLE NOW ON THE MIND SMOKE ALBUM PAGE

It was a drizzly foggy night on Thanksgiving Eve 1979. The aura of tryptophan mixed with beer, cheap booze and hormones filled the Silver Dollar Saloon as the Freelance Vandals took the stage. WBAB, a popular radio station, was on hand to capture the band's first radio show!