1961

20-Year-Old Singer Is Bright New Face at Gerde’s Club

"A bright new face in folk music is appearing at Gerde’s Folk City. Although only 20 years old, Bob Dylan is one of the most distinctive stylists to play a Manhattan cabaret in months.

Resembling a cross between a choir boy and a beatnik, Mr. Dylan has a cherubic look and a mop of tousled hair he partly covers with a Huck Finn black corduroy cap. His clothes may need a bit of tailoring, but when he works his guitar, harmonica or piano and composes new songs faster than he can remember them, there is no doubt that he is bursting at the seams with talent.

Mr. Dylan’s voice is anything but pretty. He is consciously trying to recapture the rude beauty of a Southern field hand musing in melody on his porch. All the “husk and bark” are left on his notes and a searing intensity pervades his songs

Mr. Dylan is both comedian and tragedian. Like a vaudeville actor on the rural circuit, he offers a variety of droll musical monologues: “Talking Bear Mountain” lampoons the over-crowding of an excursion boat, “Talking New York” satirizes his troubles in gaining recognition and “Talking Havah Nagilah” burlesques the folk-music craze and the singer himself.

In his serious vein, Mr. Dylan seems to be performing in a slow-motion film. Elasticized phrases are drawn out until you think they may snap. He rocks his head and body, closes his eyes in reverie and seems to be groping for a word or a mood, then resolves the tension benevolently by finding the word and the mood.

He may mumble the text of “House of the Rising Sun” in a scarcely understandable growl or sob, or clearly enunciate the poetic poignancy of a Blind Lemon Jefferson blues: “One kind favor I ask of you--See that my grave is kept clean.”

Mr. Dylan’s highly personalized approach toward folk song is still evolving. He has been sopping up influences like a sponge. At times, the drama he aims at is off-target melodrama and his stylization threatens to topple over as a mannered excess.

But if not for every taste, his music-making has the mark of originality and inspiration, all the more noteworthy for his youth. Mr. Dylan is vague about his antecedents and birthplace, but it matters less where he has been than where he is going, and that would seem to be straight up." (Robert Shelton, NY Times Sept 29, 1961)

1965

"Taking the first, electric side of Bringing It All Back Home to its logical conclusion, Bob Dylan hired a full rock & roll band, featuring guitarist Michael Bloomfield, for Highway 61 Revisited. Opening with the epic Like a Rolling Stone, Highway 61 Revisited careens through nine songs that range from reflective folk-rock (Desolation Row) and blues (It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry) to flat-out garage rock (Tombstone Blues, From a Buick 6, Highway 61 Revisited). Dylan had not only changed his sound, but his persona, trading the folk troubadour for a streetwise, cynical hipster. Throughout the album, he embraces druggy, surreal imagery, which can either have a sense of menace or beauty, and the music reflects that, jumping between soothing melodies to hard, bluesy rock. And that is the most revolutionary thing about Highway 61 Revisited -- it proved that rock & roll needn't be collegiate and tame in order to be literate, poetic, and complex." (All Music)

1966

"By melding down-home blues with Beat poetry and Shakespearean lyricism, Robert Zimmerman reached the zenith of his musical genius with this 1966 masterpiece, released 50 years ago today (May 16, 1966). The vivid imagery, organic instrumental warmth, and paeans of love and heartbreak are spellbinding. It's Dylan's ultimate sell: Blonde on Blonde is as confident and divinely artistic as he wanted us to believe he always was. He said that it came closest to recreating the "thin, wild mercury sound" in his head. In other words, it's Dylan at his most Dylan.

As the first double LP in rock music, Blonde on Blonde is the finale for his trilogy of albums released over 15 months in '65 and '66, beginning with Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited. Dylan was settling into his new identity as a bonafide rock star. The young man who was the musical entertainment at Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech three years earlier buried his folk singer beginnings with his electric debut at Newport Folk Fest, and he was amid a frenzied run of plugged-in breakthroughs.

But Blonde on Blonde started in New York City with a thud. After five recording sessions -- almost the entire time it took to record Highway 61 Revisited, and two days more than it took to record all of Bringing It All Back Home -- Dylan had finished just one song. The sessions with his backing group, The Hawks -- later to be known as The Band -- were missing something. That something was in Music City.

At producer Bob Johnston's suggestion -- and despite protests from Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman -- Dylan and organist Al Kooper and guitarist Robbie Robertson flew to Nashville for sessions in February and March of '66.

At Columbia's A Studio on Nashville's Music Row, Dylan, Kooper, and Robertson were joined by top session musicians, including harmonica player, bassist, and guitarist Charlie McCoy, drummer Kenny Buttrey, and pianist Hargus "Pig" Robbins. Johnston removed the studio partitions, positioning the new group tightly together for maximum groove. The result was a familiar-sounding country-blues band providing the canvas for an artist at his peak to paint emotive, impressionistic images in his own poetic style.

Blonde on Blonde is the sound of Bob Dylan's America. The land of Woody Guthrie, Chuck Berry, Mark Twain, Coca-Cola, Walt Whitman, Levi's, barroom poker games, Cavalry General George Custer, Jack Kerouac, and other characters from bygone eras.

In our hyper-connected, info-gobbling digital age, cornerstone artists like Dylan and works like Blonde on Blonde are ever more rare. If there was a National Gallery of Art for music displaying the country's priceless works of sound, Dylan's Blonde on Blonde would be one of the stars (Disliking Blonde on Blonde is essentially an act of treason). It is, arguably, Dylan's best work. And in the story of America, Dylan is one of our greatest characters and authors." (Billboard Magazine 2016)

1967

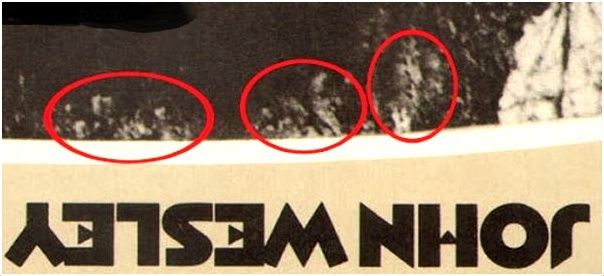

"Legend has it that you can see the Beatles in Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding. Look closely; etched into a tree at the top of the album’s cover, there are the visages of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. The photographer John Berg acknowledged the presence of the Fab Four in the image, just once, vaguely. 'It’s like Dylan; very mystical,' Berg told Rolling Stone in early 1968. By this time, Dylanology had taken hold, with writers craning their necks to examine the runes in every scrap of output. There was a hunger for mythos. In Dylan, fans and journalists had found a local god worthy of a shrine. Even when there was hardly anything to understand — the misidentified carvings of a band’s image in a tree on an album cover? — meaning could be affixed to his detritus. Dylan was the ultimate projection, the proverbial rabbit hole to crawl down. It happened so quickly.

In 1967, while the actual Beatles licked an acid stamp and postmarked it c/o Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Brian Wilson composed a teenage symphony to God, and the Velvet Underground unhooked the daisy chain linking the Summer of Love, Bob Dylan sat in a basement writing. He got there by accident. With the sun in his eyes, likely peeling around the hilly turns of Striebel Road in Woodstock, New York, near his manager Albert Grossman’s home, Dylan lost control of his Triumph motorcycle. He crashed. Prior to the 1966 accident, Dylan had released a new album approximately every eight months since 1963, a steady beat gaining volume until Blonde on Blonde, the summation of Dylan’s folk-rock fusion wracked by confusion, sadness, and new love. Despite ascending to the height of American culture, it wasn’t a happy time in his life. 'Everything was wrong, the world was absurd,' Dylan wrote in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, describing the discomfort of being hounded by fans and the press seeking meaning in his work. 'The voice of a generation' had become a persistent moniker, one that Dylan despised, and still does. Guzzling amphetamines while on a tour that felt like it would never end, Dylan began to ask himself why he was playing music in the first place. The accident arrived at a time of personal waywardness, creating the freedom to exit the public eye. He took the chance, canceling tour dates and disappearing from view.

Recovering first in the third-floor bedroom of his doctor’s home and then in Hi Lo Ha, his house in Woodstock’s Byrdcliffe neighborhood, Dylan grew stronger, but hardly left his home. When he did, it was to trek to a pink shack in nearby Saugerties with some pals from his band. He spent time reading and meeting with friends like Allen Ginsberg. He grew closer to his new wife, Sara Lownds; their firstborn child, Jesse; and soon their second, Anna. And he worked, steadily.

Dylan's only journey came later in the year, on a key trip to Nashville to record with local musicians. What transpired in those sessions across 1967 is one of the most significant periods in the artist’s life, about which there is little known. Gathering in New York with the members of his touring band, the Hawks, he wrote joke songs and reimagined American folk and blues. 'We weren’t making a record. We were just fooling around,' Hawks leader Robbie Robertson said. In 1990, Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin wrote: 'A quarter of a century on, Dylan’s motorcycle accident is still viewed as the pivot of his career. As a sudden, abrupt moment when his wheel really did explode. The great irony is that 1967 — the year after the accident — remains his most prolific year as a songwriter.' The crash has been accepted into lore as a life-altering event. It’s a genuine butterfly effect, scrutinized repeatedly for more than 50 years. For some, it marked the end of a great artist’s peak. For others, it unlocked a more mysterious and rewarding lifetime to come.

John Wesley Harding was released in the final week of 1967. It was the first America had heard from Dylan in more than 18 months. It was not at all what people expected from the voice of their generation. Dylan asked Columbia to release it with “no publicity and no hype, because this was the season of hype,” he said at the time. Columbia president Clive Davis pressed Dylan to release a single with the album, but he refused. On the much-analyzed cover, a squinting Dylan wearing a cheshire cat grin is surrounded by Luxman and Purna Das, two South Asian musicians brought to Woodstock by Grossman, and Charlie Joy, a local stonemason and carpenter. What did these men know that we don’t?

In Dylan’s absence, he had become something more than just a popular singer or a rock star. He became a proper subject. Earlier in 1967, the documentarian D. A. Pennebaker released Don’t Look Back, the first of the Dylan films, this one trailing him as he jostles with peers, the press, and his own outsize persona. Dylan was even set to publish a volume of poetry, circling the square of pretension. There is no modern-day analogue to Dylan’s disappearance; constant presence is the very economy of celebrity...Taking 18 months off is to tempt the fates. For Dylan, it was a salve.

John Wesley Harding is a plaintive record, milder in tone, largely unplugged, and more direct. It is almost entirely acoustic, a distinct departure from the ramshackle electric sounds of 1965. 'Every artist in the world was in the studio trying to make the biggest-sounding record they possibly could,' producer Bob Johnston recalled. 'So what does Dylan do? He comes to Nashville and tells me he wants to record with a bass, drum and guitar.' And unlike the sweeping emotional grandeur of Visions of Johanna...Dylan’s eighth album has a kind of campfire quality. He’s telling stories, and we can’t always pick out the hero.

He began recording just two weeks after the passing of his hero Woody Guthrie. There are strands of Guthrie’s righteous, surefooted moral clarity in these songs. These are songs about people, draped in rectitude and clear-eyed sentiment. He commits the sin of I, using the first person in five of the album’s song titles. It is, in its way, straightforward. 'What I’m trying to do now is not use too many words,' Dylan said in a 1968 interview. 'There’s no line that you can stick your finger through, there’s no hole in any of the stanzas. There’s no blank filler. Each line has something.'

Dylan played at Woody Guthrie’s memorial concert in 1968 and then largely vanished from view again. 'One day I was half-stepping, and the lights went out,' he would later say. 'And since that point, I more or less had amnesia. … It took me a long time to get to do consciously what I used to be able to do unconsciously.' He was just 25 years old when the lights went out. Twice that lifespan has since passed, and we still don’t really know what happened in 1967, other than what we can still hear." (Nothing Is Revealed: Bob Dylan in 1967 and Elsewhere, Sean Fennessey, The Ringer)

1975

"From the very start Dylan had his sights set high and knew he stood out from the other musicians working the circuit. As he recalls, 'There were a lot of better singers and better musicians around these places but there wasn’t anybody close in nature to what I was doing. Folk songs were the way I explored the universe, they were pictures and pictures were worth more than anything I could say. I knew the inner substance of the thing. I could easily connect the pieces…Most of the other performers tried to put themselves across, rather than the song, but I didn’t care about doing that. With me, it was about putting the song across.'

His repertoire also stood out from the other folksingers as 'it was more formidable than the rest of the coffee-house players, my template being hard-core folk songs backed by incessantly loud strumming'.

However, he was also feeling the need to write his own songs rather than becoming just another cover artist. 'I wanted to understand things and then be free of them. I needed to learn how to telescope things, ideas. Things were too big to see all at once, like all the books in the library – everything laying around on all the tables. You might be able to put it into one paragraph or into one verse of a song if you could get it right.'

But the slick pop-oriented single was not on his agenda. 'I agonized about making a record, but I wouldn’t have wanted to make singles, 45s – the kind of songs they played on the radio. Folksingers, jazz artists and classical musicians made LPs, long-playing records with heaps of songs in the grooves – they forged identities and tipped the scales, gave more of the big picture. LPs were like the force of gravity. They had covers, back and front, that you could stare at for hours. Next to them, 45s were flimsy and uncrystallized. They just stacked up in piles and didn’t seem important.'

On 16th September 1974, Bob Dylan entered A & R Studios in New York to begin recording Blood on the Tracks. The studio was of course the magical place where he recorded his first 6 albums. His original producer John Hammond joined him in the studio on this night, an ‘historic moment’ for them both. Also with Bob was his girlfriend Ellen Bernstein. Studio boss Phil Ramone was at the engineer’s desk, with Glenn Berger as his assistant. Bob started the session warming up to the task with just himself, guitar and harmonica, reaching for the voice that would define Blood on the Tracks.

Widely considered to be one of his strongest albums, Blood on the Tracks is often referred to as his divorce album although Dylan strongly contends this sentiment. However, it was quickly written and recorded after his marriage with Sara Lowndes collapsed and novelist Rick Moody has since called it 'the truest, most honest account of a love affair from tip to stern ever put down on magnetic tape.'

Many of the songs are almost impressionistic in feel as it was inspired by and recorded after he studied painting with Norman Raeban. Dylan does concede his artistic venture did estrange him from his wife. 'It changed me. I went home after that and my wife never did understand me ever since that day.'" (NY Times)

1997

"Just when it seemed like Dylan’s creative fire had waned—he hadn’t released an album of new material in six years—he produced 1997’s Time Out of Mind, his second collaboration with producer Daniel Lanois. The album, a riveting, unflinching look at lost love and mortality, drew comparisons to Blood on the Tracks and earned him three Grammy Awards, including album of the year. His music, Dylan said at the time, endures because it is built on the foundation of folk music of Muddy Waters, Charley Patton, Bill Monroe, Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie. 'I really was never any more than what I was—a folk musician who gazed into the grey mist with tear-blinded eyes and made up songs that floated in a luminous haze,' he wrote in Chronicles, the first volume of his memoir. 'I wasn’t a preacher performing miracles.'” (Smithsonian Magazine)

“These so-called connoisseurs of Bob Dylan music, I don’t feel they know a thing or have any inkling of who I am or what I’m about. It’s ludicrous, humorous, and sad that such people have spent so much of their time thinking about who? Me? Get a life, please. . . . You’re wasting your own.” — Bob Dylan, 2001

The Dylan generation gap

“I’ve never heard of Bob Dylan.”

"For those who came of age when Dylan was, in essence, their generation’s musical supreme being, such blasphemy may be too mind-blowing for a boomer to believe.

But according to an unofficial, one-night-only survey, this was actually not an uncommon response. Nearly 25 percent had absolutely no clue who he is, and another 20 percent only had a vague idea. That means half of the respondents were either completely or mostly oblivious to the artist who, like the one they were there to see, is regarded as the voice of a generation. Ranging in age from 12 to 30, most were millennials in their 20s — about the age many of Dylan’s original fans were when they first heard the folksinger.

Dylan’s legacy has stood the test of time — and 2016’s Nobel Prize for Literature didn’t hurt. And he’s made a nearly lifelong, iconic career of not seeming to care what other people — young or old — have to say about him." (www.sunsentinel.com)

"OK, a lot of people say there is no happiness in this life and certainly there’s no permanent happiness. But self-sufficiency creates happiness. Just because you’re satisfied one moment — saying yes, it’s a good meal, makes me happy — well, that’s not going to necessarily be true the next hour. Life has its ups and downs, and time has to be your partner, you know? Really, time is your soul mate. I’m not exactly sure what happiness even means, to tell you the truth. I don’t know if I personally could define it." (Bob Dylan)

"Dylan writes lyrics that are textured and capacious enough to withstand endless reinterpretation. A common experience when seeing him live is to discover that a song that you thought was about rage is suddenly transformed into something tender. Ten years on, at another concert, that same song you now think of as tender turns out to be a wry throwaway burlesque. The burlesque later becomes an elegy. And on it goes.

We’re listening to a man forever in search of God. People talk of Dylan “finding Jesus” in the late 1970s just as they talk of him being a “political protest singer” in the 60s. But the truth is the reverse: Dylan is perpetually looking for God and his protest is political only because underneath it is (and always has been) existential. He is often explicitly protesting against injustice, sure, but he is also making incandescent protest against the indifferent universe. He is concerned with spirituality in its deepest sense – the quest for human dignity and meaning – and he long ago renounced the formal strictures of Christianity or Judaism. In 1997, he said: “I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else … The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.”

We are listening to an artist who has studied and absorbed the poets that have gone before him. “I contain multitudes,” he sings in Rough and Rowdy Ways. Many books have been written about his reading and refiguring of Blake and Keats and the Beats; of Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Rilke; of Chaucer and Auden and Eliot and Yeats. The list is endless. Then there’s his ever-evolving reading of the Bible, and the way all of those cadences and testaments reverberate in his work. In the later albums, he has been steeping himself in the ancients. Sometimes he is communing with Ovid – redeploying lines, summoning up Ovidian ideas of exile, of fame and alienation, of living too long, of staying alive by writing poetry, of living for ever. Other times, he is singing that he has fallen in love with Calliope, foremost of the muses in Greek mythology and the patron of epic poetry.

Which brings me to what I think we’re celebrating most of all: Dylan’s generosity. Because Dylan, like Shakespeare and Homer, is an artist who disappears as only the greatest can. An artist who somehow creates work far beyond himself. We have no idea what Shakespeare feels. You look for him in the plays – all the way from Juliet to King Lear via Bottom and Cleopatra – and you can’t find him: he has mysteriously vanished from the work altogether. Same with Dylan. Sure, the songs come through him and by him but they’re not for him. They are there for the benefit of anyone and everyone who wishes to fathom human nature in their company. They exist for all the world today and they will exist for all the world tomorrow. They will always be there for me. They will always be there for you." (The Guardian)

“The future for me,” Bob Dylan sang in 2001, “is…a thing of the past.”

"Look, you get older. Passion is a young man’s game. Young people can be passionate. Older people gotta be more wise. I mean, you’re around awhile, you leave certain things to the young. Don’t try to act like you’re young. You could really hurt yourself." - Bob Dylan

Couldn't Shake It If I Tried

Jim Treulein, a longtime veteran of the local music scene, is widely known as a "songfinder" whose mastery of the Americana genre always captures the hearts of a live audience. His latest release, Couldn't Shake It If I Tried, is an excellent collection of Americana songs by local songwriter Dee Harris.

The Lost Tapes Vol. 2

This wild & loose proto-punk band always conjures up an atmosphere of Chuck Berry meets The Ramones with a side order of Blonde on Blond Bob Dylan.

Return To All Blog Posts