Today, I thought it would be cool to look back on 6 albums

that pretty much got lost in the proverbial sauce back in the 70's

1971: LAURA NYRO & LABELLE : GONNA TAKE A MIRACLE

From the first time I listened to Laura Nyro's music, I became a true fan of her work. I recently came across a wondeful article from The Afterword which does justice to Nyro's beautiful Gonna Take A Miracle album.

"Laura Nyro's first album for Columbia, Eli And The Thirteenth Confession, is the one with exuberant, uplifting songs. The second, New York Tendaberry is more introspective but full of gospel fervor. The third, Christmas And The Beads Of Sweat, is R&B on side one, assisted by the hundred carat soul pedigree of The Swampers from Muscle Shoals, and almost a symphony on side two. All three aspects came together for Gonna Take A Miracle, her fourth and contract ending album: exuberance, gospel and R&B.

It is easy to assume Gonna Take A Miracle, an album of covers, probably the first of its kind by an artist who primarily writes their own material, is a half-hearted contractual obligation record but nothing could be further from the truth. It’s a carefully thought-through expression of an artist’s heart and soul that could only be achieved in collaboration with a group of sisters, sympathetic and supportive producers and stellar musicians.

The album had its germ of origin on the album, Christmas And The Beads Of Sweat, when Laura covered Up On The Roof, a Goffin/King composition originally performed by The Drifters. Putting a list of songs together that they all loved was the easy part. Recruiting Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, just as they were launching the Philadelphia International Records label, was a masterstroke. Their feel of the material was second to none and their production skills exemplary. They also had a book full of ace musicians to call on: Norman Harris & Roland Chambers guitar, Ronnie Baker bass, Jim Helmer drums, Lenny Pakula organ, Larry Washington & “Liberty” Mata bongos and Vincent Montana Jr. percussion, all gathered together for two weeks at Sigma Sound Studios.

The keys that unlocked the magic were the arrangements. Any preconceptions Gamble and Huff had, or Laura herself, were quickly abandoned. As excited as she was at the prospect of playing with these musicians, they, on the other hand, struggled to adapt to her quirks and foibles. It took a little while, a great deal of discussion and considerable patience to lock into her groove and accommodate her dynamism. A great fan of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, who had supported her in full-on Bitches Brew mode at The Fillmore East, she had McCoy Tyner-esque pedal points and fourth chords. Gamble and Huff needed to shape the R&B of the band around Laura’s stylings and LaBelle’s doo-wop gospel while staying true to the songs. They did so with affection and warmth and a little help from their friends, Thom Bell for the strings and Bobby Martin and Pakula for the horns.

Straight away, the album puts us in the subway of Laura’s youth as she sings her heart out with the three women, singing in the round, a capella, accompanied only by handclaps and finger snaps, each taking a line in turn. The song is I Met Him On A Sunday by The Shirelles, issued in 1958, a perfect example of favorite teenage heartbeat music as Laura described it. They go straight to their wellspring of joy. It’s impossible to listen to it without being uplifted. Laura, Patti, Nona and Sarah must have felt like teenagers again. However, it segues into The Originals’ The Bells, a performance that implodes lost innocence almost halfway through. These are not women on a nostalgia trip. They are grown, matured, experienced, damaged even, but no less passionate and no less subject to the vagaries of love. The vocals swoop and holler over Thom Bell’s restrained strings, almost, but not quite, untethered and deranged. Marvin Gaye had co-written and produced the song for his backing group but this version puts the backing vocalists on an equal footing with the lead and keeps the production to a minimum.

The Medley of Monkey Time/Dancing In The Streets is where the party starts with purses on the floor and snakebite for fuel. Major Lance and Martha Reeves have never felt so free and uninhibited. There is no hint of insurrection here. They take on face value the exhortation to dance. It’s track three of ten and the band kick in properly for the first time. Helmer’s drumming keeps Laura’s piano sharp. She is definitely the focal point, taking the lead throughout, with LaBelle proclaiming encouragement. By the last minute, when the horns finally play the famous riff and the repeated ‘don’t forget The Motor City’, the girls have kicked off their shoes, let their hair down and are waving their arms above their heads.

Desiree is the secret teenage crush hidden in a private diary. An obscurity by The Charts, its place on the album seems odd, sandwiched between two big dance numbers, until you realise that Laura’s longest relationship, one lasting most of her adult life, was with Maria Desiderio. LaBelle are solemn and attentive as they cross their hearts and swear to die. Its quiet simplicity, just piano, vibraphone and voices, is its beauty.

You Really Got A Hold On Me is another signature tune for Tamla Motown and Smokey Robinson in particular, and was thrillingly covered by The Beatles no less. As such, it has a special place in every music lover’s heart. In 1973, it was a bold decision to do another version. Whereas Smokey just seemed to want a hug and Lennon was vulgar in his desire for sex, Laura and LaBelle begin with the confused kindling of first love. Then, hormones enraged by the relentless rhythm section, the ecstasy in the voices increase and there is no denying they are experiencing a collective sexual awakening. It’s a remarkable conclusion to side one. First up on side two, Spanish Harlem has the feel of a morning after. LaBelle’s role is performed by horns that maintain a discrete distance, as though they are birds in a tree outside, as Laura wakes with her Spanish rose, “with eyes as black as coal, that look down into my soul/And starts a fire there and then I lose control.” As Aretha had already proved, it’s a song that suits the female voice extremely well, and there is tone in Laura’s, a belief, as her heart opens up, like a flower blossoming, that tells us love is a miracle.

Within one more heartbeat, another boy catches her eye. Jimmy Mack is free, relaxed and glad to be alive. The groove rolls around the piano just as the LaBelle’s backing ‘woo’s envelope the lead voice and, again, the handclaps take us to the street corners of the Bronx. The Wind is the oldest song, a doo-wop classic by Nolan Strong and the Diablos, released when Laura was a child. They treat it with respect, the voices harmonizing beautifully, anchored by a quiet piano and vibraphone. It’s nostalgic about a lost love, a wistful daydream before the big finish.

Nowhere To Run, a third Martha Reeves and The Vandellas song, is a tour de force. The Motown original is built on the rhythm section of Bennie Benjamin and James Jefferson. Baker’s bass pops and squirms as brightly as Jefferson’s and tambourine and handclaps solidify the beat, but, on this version, it’s the vocals that steal the limelight. The song is stretched to double its length by inventive harmonizing of the title phrase, spinning with delight rather than twisting with the paranoia of the words themselves. The effect is hypnotic. The finale is the title track, a song of heartbreak originally by the girl group The Royalettes. It is entirely built around Laura’s emotional range from hushed sorrow to a roaring grief, LaBelle matching her all the way, cushioned by a sensitive string arrangement and Laura’s own piano.

These ten tracks, eleven songs, five of which are Tamla Motown, map a route around and through a young girl’s heart. These are songs designed to move an audience both physically and emotionally. Revisited and refashioned by grown women, they carry greater resonance. Gonna Take A Miracle is an album about an individual, the best expression of her career, but, also, that of a collective, a group. It captures the conflict and dichotomy of adolescence, being both shy and brazen at the same time. Laura Nyro was known as a singer/songwriter, bracketed with Carole King and Joni Mitchell, someone who created and performed music essentially by herself. She could have made another inward looking album like Tapestry or Blue but, instead, opened herself up and rejected her categorization and immersed herself in a collective endeavor. On an album consisting entirely of other people’s songs, she found the perfect vehicle to articulate the myriad aspects of her personality. It’s also an album of liberation, a shrugging from the shoulders of the burdens of responsibility, the responsibility of living up to the music business’s unrealistic expectations. It’s the sound of Laura Nyro pleasing herself.

Laura Nyro intended Gonna Take A Miracle to be her swansong as she retired to quiet domesticity as soon as recording finished. The dark cloud that overshadows this album is that at the tender age of twenty-four, Laura Nyro was worn out, to such a degree she felt old before her time and longed for her ‘youth’. She wasn’t hard-wired to cope with fame, struggled with the attention it brought, the hyperbolic marketing and suffering from crippling stage fright.

Her marriage failed, she had a son by another lover and made a comeback in 1975 when she regained control of her music and her destiny. She observed the business from the arm’s length of a lower-key career, focussing on evolving her art and balancing her need to express herself with a full family life. She set up home with Maria Desiderio and lived happily ever after. She died at the age forty-nine of ovarian cancer, the same age and disease as her mother.

Gonna Take A Miracle is a crowd-pleaser of an album that demonstrates the power of music to bring together people from different backgrounds and cultures. Recorded at a time when musical tribes were fracturing, it speaks to kinship and common ground, about how we, as humans, are basically the same, with similar experiences and feelings. It’s about caring and sharing and bringing out the best in each other. It tells a love story, a public one with music with a hint of a personal one with Maria. The music within the LP’s grooves is more positive and hopeful than any other record released in that bumper year of 1971. Gonna Take A Miracle is a small miracle in itself, enough to make you believe in true love and restore your faith in the ability of the even the most fragile amongst us to stand firm and assert their true personality."(https://theafterword.co.uk/fifty-years-of-gonna-take-a-miracle/)

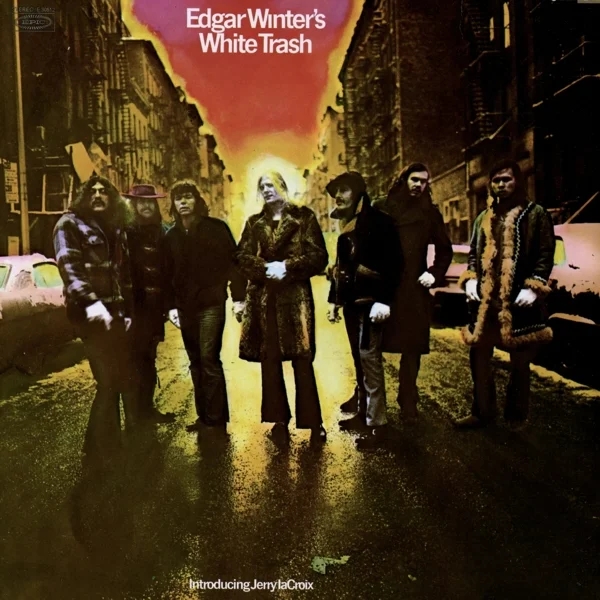

1971: EDGAR WINTER'S WHITE TRASH

Ah yes, I remember listening to this slab of vinyl while I was at the University of Dayton out in Ohio back in the 70's. I enjoyed Edgar Winters first album, Entrance, and was just as pleased with Edgar Winter's White Trash album. The main reason I think this is a “lost album” is that the album has definitely been forgotten over the years. Wind up your turntables folks!

Here's A Wide Variety Of Reviews

Jon Landau, Rolling Stone Magazine 1971: "The sound of the band is loose and rangy in the best tradition of white Southern R&B (a la the best of John Fred and His Playboy Band) and Winter's singing is fully equal of it: he never stops at mere competence. On a quick listen some of the music could have easily been mistaken for Stax soul. But the difference is in the white gospel roots that both Winter and co-vocalist Jerry laCroix exhibit throughout the record. Up-tempo songs like "Save the Planet" and "Keep Playin' that Rock and Roll" are fine rockers but the guts of the album is in slow, semi-religious "You Were My Light." The latter is the highlight of the album: Winter sings flawlessly, first in front of his superb rhythm section, and then with a beautifully arranged and blended horn section. On the choruses the three elements come together with tremendous impact -- enough to blow me back listen after listen. The lyrics here, as throughout, are almost charming in their openness, directness, and simplicity. Perhaps the biggest surprise of the album is the emergence of Edgar Winter as an excellent songwriter.

At the peak of their frenzy, both Winter and LaCroix cross over the gospel line and into pure shrieking and screaming. In the controlled doses they administer here, it is very powerful stuff. Such vocal techniques are easily misused, but like everything else on White Trash, Edgar keeps it under control and makes it work for him. The results are a revealing and exciting album -- hopefully, only the first of many more to come. It's the kind of record that makes you want to see the group perform. What higher praise is there for a new album by a new group?"

Don Heckman, Stereo Review 1971: "Edgar Winter, brother of the more highly-publicized Johnny and one of the most adept performers on today's pop scene, is having difficulty putting it all together. Clearly, his skills trace to a jazz-blues background (he is a good enough saxophonist to play with most major jazz groups), yet Columbia seems intent upon transforming him into a heavy-rock star.

Given that decision, however, the group Winter has assembled includes the sort of players who can make it work -- who should make it work. Paired with him in the front line is tenor saxophonist/singer Jerry LaCroix, a solid talent in his own right; the back-up ensemble of trumpet, tenor saxophone, and rhythm section plays with self-assured professionalism and the down-home raunchy-rock South Texas blues feeling Winter is reaching for. The problem, for me, is that the qualities that make Winter most interesting -- his fine technical skills both as a saxophonist and a keyboard player, for example -- are shunted aside in favor of his singing, and in favor of his generally derivative compositions (usually written in collaboaration with LaCroix). Winter's vocals are peculiarly hard to pin-point; sometimes he sounds like Joe Cocker, sometimes like Leon Russell, and only rarely like an exciting new singer. I assume the higher-pitched, wailing voice that carries most of the harmony lines is LaCroix's; it sure doesn't do much to improve the music."

1973: BIG STAR - RADIO CITY

As I've seen over the decades some magnificent rock bands never seem to make it and Big Star is a perfect example of that. Big Star had been around in the 60's instead of the 70's, they would have certainly been able to have been as iconic as Buffalo Springfield or The Byrds.

“Instead, Big Star found themselves terribly out of time as a brilliant pop band sitting at odds amongst the glam and bluesy rock of the early 70s. Their second album Radio City is probably their best. It’s full of bright, shining pop songs with a touch of Southern soul alongside the trebly guitars and keening lyrics that seem to constantly reflect on a lost adolescence. Alex Chilton had previously enjoyed success with chart toppers the Box Tops but here, following the departure of songwriting foil Chris Bell, he came into his own. The chugging melodic songs such as ace in the hole September Gurls basically invented the career of bands like Teenage Fanclub. However, Big Star struggled to get noticed and it was only when bands such as R.E.M. and the Replacements started name checking them that their music started to get rediscovered.” (normanrecords.com)

"Jody Stephens, drummer of Big Start stated that “was filled with enthusiasm for the band's #1 Record. Fresh, new and exciting, with hints of The Beatles, Badfinger and The Byrds in its musical DNA, Big Star’s debut album was championed by legions of enthusiastic rock critics but met with public indifference. The blame for that was laid at a distribution network that failed to get the album into record stores. After the departure of guitarist Chris Bell, pushed the remaining band members to create another album.

The band became a three-piece, and all had a little bit of a larger role to play musically. And because there were just three of us, there was a lot more space we could do something with, or not. So, there was a lot more opportunity, and, certainly, it helped with our evolution and changed the character of the band.

Stylistically, the band's 2nd album, Radio City, picked up from where #1 Record left off, blending taut rock’n’roll (O My Soul) with dreamy power-pop (September Gurls) and reflective acoustic ballads (I’m In Love With A Girl). Suddenly, there was more of a worldly outlook on the band's lyrics and music.

Released in February 1974, Radio City boasted striking artwork featuring front and back cover photographs by William Eggleston. The front cover, called The Red Ceiling, ‘was taken in Mississippi and was part of his catalogue of photographs and Alex was the one who picked it out.’" (udiscover.com)

1973: Neil Young - Time Fades Away

I remember buying this album at a record shop called The Forest during my college years in Dayton, Oh after I happened to go to see a Neil Young concert at Cincinnati Gardens. The concert itself had a dark vibe to it.

SET LIST @ CINCINNATI GARDENTS

01. On The Way Home

02. I Am A Child

03. Sugar Mountain

04. Out On The Weekend

05. Harvest

06. Old Man

07. Heart Of Gold

08. The Loner

09. The Last Trip To Tulsa

10. Don't Be Denied

11. Time Fades Away

12. Alabama

13. New Mama

14. Lookout Joe

15. Cinnamon Girl

16. Southern Man

17. Are You Ready For The Country?

18. Last Dance

Neil Young was still laid up at his Broken Arrow ranch, just south of San Francisco, recovering from spinal surgery, when Harvest made him the biggest-selling solo artist in the world. During the long months of his recuperation, there had been a growing clamor for him to tour that had gone unanswered, although he knew there were big bucks to be made by everyone after the album’s phenomenal success.

The same month, Neil Young started to assemble a large crew of technicians at his ranch to prepare for a three-month, 65-date tour, the largest and longest of its kind to date, which would find him playing nightly to audiences of up to 20,000 people in sports stadiums, basketball arenas, ice hockey rinks. Also at the Broken Arrow ranch were The Stray Gators, the band who’d played on Harvest, including veteran Nashville session drummer Kenny Buttrey, bassist Tim Drummond, pedal-steel player Ben Keith and on keyboards Jack Nitzsche, the producer and arranger who’d first worked with Young on his Buffalo Springfield epic, Expecting To Fly.

They would be his backing band on the forthcoming tour, rehearsals for which were interspersed with recording sessions for the official follow-up to Harvest. Young had already recorded four solo acoustic demos at A&M studios in LA – “Letter From Nam”, “Last Dance”, “Come Along And Say You Will” and “The Bridge” – and worked up more new songs at Broken Arrow. The new record’s working title was ‘Last Dance’. There was even a track listing for it that included the songs “Time Fades Away”, “New Mama”, “Come Along And Say You Will”, “The Bridge”, “Don’t Be Denied” on side one, with “Look Out Joe”, “Journey Through The Past”, “Last Dance” and “Goodbye Christians On The Shore” completing the album.

As the recordings and rehearsals continued and perhaps the scale of the tour he was about to start became increasingly apparent, Young grew ever more fretful about his physical condition. He hadn’t played electric guitar on stage since a CSNY concert in Minneapolis on July 9, 1970. For most of the past 12 months, because of his debilitating spinal condition, he’d had to wear a back brace which sometimes made playing even acoustic guitar painful, and he’d therefore made only one public appearance during the last 18 months, at the Mariposa Folk Festival in Ontario in July 1971. With the tour now looming, he began to worry that he wouldn’t be able to carry an entire show on his own.

What became know as the ‘Time Fades Away’ tour opened on January 4, 1973, at the Dane County Coliseum in Madison, Wisconsin, and it was fraught from start to finish. Young would later describe it as one of the unhappiest times of his life, probably the worst tour of his career.

He’d already fallen out with the band, over their demands for more money than they’d originally signed up for and when they weren’t on stage, travelling together on the turbo-prop Lockheed Elektra jet Young had chartered for the tour, he tended to keep his distance from them. He stayed on separate floors in hotels, retreating to his room after most shows to get drunk on tequila and stoned on pot.

After only a few shows, he became frustrated with the way the band were playing, how they sounded in the cheerless arenas into which they’d been booked. His mood was worsened by the behavior of the crowds. They were distracted and noisy during the acoustic parts, restless and inattentive elsewhere. Most had come to hear their favourite songs from Harvest. They were noisily indifferent to anything they were unfamiliar with, which turned out to be a lot. At least a third of every show was devoted to new songs, previously unheard. These were emotionally raw and came from a much darker place than Harvest.

Young’s performances became increasingly erratic, prone to hysteria, confrontational. He took to berating audiences. More than once, enraged, he quit the stage and took the startled band with him. There were few nights when Neil didn’t throw a major strop. His moods took a toll on everyone, especially the crew, who struggled with the inadequacies of the custom-built PA and the inhospitable acoustics of the huge sheds they were playing. Neither did the band escape his often boozy wrath. Kenny Buttrey had made his bones as a studio drummer, in which environment he had few equals. Nothing he played on tour seemed to satisfy Neil, however, and none of it was loud enough, even though he used bigger and bigger sticks and hit the drums so hard his hands bled. After 33 shows, he was replaced by Johnny Barbata, who’d played on the last CSNY tour.

By now, with a month of the tour left, Young’s voice was giving out. David Crosby and Graham Nash signed up for the last three weeks, although what they could have done to lighten the sour mood that had settled on things is unclear. Crosby’s mother was dying of cancer and Nash’s girlfriend had just been murdered by her brother in a drugs-related killing.

There was one more flashpoint. On March 31, the ‘Time Fades Away’ tour fetched up at Oakland Coliseum, where during a version of “Southern Man”, Young saw a cop laying into a fan. “I can’t fuckin’ sing with this happening,” he announced, storming off, as the angry crowd pelted the stage with bottles.

Three nights later, on April 3, in Salt Lake City, after exactly 90 days, the ‘Time Fades Away’ tour was finally, to the relief of everyone, over.

Back at Broken Arrow, Young’s mood was dark. He continued to brood over Whitten’s death, which took on a symbolic significance. Whatever he released next, in other words, would have to recognize the harsh new realities he’d recently had to face. In his present mood, the winsomeness of Harvest was far beyond him.

Early in 1971, a double live album had been announced, along with a track listing. It had never been released. Now, however, Young’s thoughts turned again to a live album. Elliot Mazer, who’d produced Harvest, had recorded 45 of the dates on the Time Fades Away tour and Young started to review them, discarding familiar songs in favorr of the new material he’d played to an often hostile reaction from an audience who’d only wanted to hear the hits they knew.

What eventually became the Time Fades Away album would reflect the strains, tensions and conflict of the recently completed tour, a documentary roughness, unflattering in many ways, but painfully honest, which was as much as Young could ask of himself at the time.

The album when it came out featured seven tracks recorded during the last month of the Time Fades Away tour, plus a 1971 live version of Love In Mind. The album opens with the six-minute title track, a feverish narrative about junkies, politicians and the military, intercut with a running dialogue between a wayward son and his weak, pleading father. Musically, you can imagine it was perhaps intended to recall something like the lean howl of Dylan’s Highway 61. Instead, it’s noisy, cantankerous, all over the place. Nitzsche’s frantic piano, high in the lop-sided mix, drowns out Young’s guitar and Ben Keith’s pedal steel. Half way through, there’s a wheezing harmonica solo, mercifully brief. Barbata should be driving all this along with some urgency, but nobody seems to have told him where the song is going and spends the entire number hammering away in the background like a man building a shed.

Yonder Stands The Sinner is no less reassuring, a demented 12-bar thrash, with Young barking the lyric like someone apparently possessed you’d walk around in the street.

The record’s three ballads – Journey Through The Past, introduced as ‘a song without a home’, The Bridge and the gorgeous Love In Mind – offer some respite on a record whose battered psychology is most bruisingly represented by the two long tracks that open and close its second side. Don’t Be Denied is graphically autobiographical, directly descended from Helpless. Its four verses cover Young’s childhood, his parents’ divorce, his troubled adolescence, the corruption of youthful optimism and the redemption offered by music.

Last Dance, meanwhile, much changed from the original A&M sessions, opens with a blast of feedback and over the next 10 minutes becomes a thing of relentless mayhem. The track has been in many ways limping towards a predictable end, and the band sound on the verge of packing up for the night, when from somewhere Young gets a second wind. ‘No, no, no,’ he starts singing, hoarsely, apparently rejecting the somewhat self-righteous message of the song so far. ‘No… No… No…,’ he goes on, screaming now. ‘NO! NO! NO!’ There’s more feedback, the band sounding confused by what’s happening. ‘NONONO!!!’ Young rants, out there, in a place you wouldn’t want to be for long. The song ends in a kind of exhausted chaos, leaving behind it an ominous silence.

Anyone who’d sat, largely appalled, through performances like this on the Time Fades Away tour would have been astonished if you’d told them they’d soon be released on a live album as a follow-up to Harvest.

Time Fades Away was released in October ’73, to the worst reviews of Young’s career to date. Young archivist Joel Bernstein, whose photo of the audience at Philadelphia’s Spectrum was used for the LP cover, printed on a paper stock that was intended over time to fade, summed up the bafflement of many.

And this is a clue to the significance of Time Fades Away. What Neil Young became, the wilful unpredictable iconoclast of subsequent legend, he started becoming here. Alone, really, of his superstar peers, he was clearly alert to the shifting mood of things and thus with Time Fades Away, he distanced himself at a stroke from the dreamy utopianism of the so-called Woodstock Nation and the sybaritic indulgence that now prevailed in the circles from which he had so dramatically with this record absented himself.

Four years before punk’s howling disenchantment, Young was already challenging the old order. By the time it came out, he had already recorded Tonight’s The Night, a tequila-soaked musical wake for Danny Whitten and CSNY guitar roadie Bruce Berry, who had recently died from a heroin OD. There would be no turning back from here." (glidemagazine.com)

1976: R. STEVIE MOORE - PHONOGRAPHY

Among the strangest album that I ever came across in the ‘70’s was Phonography by the one and only R. Stevie Moore.

"Phonography was lo-fi legend R. Stevie Moore's first vinyl release - only 100 copies were pressed in 1976. The album (including a slightly larger 1978 pressing) barely earned the artist lunch money. But Phonography has since become the cornerstone of the Do-It-Yourself movement, while establishing Moore as the Granddaddy of home recording. Both Rolling Stone and Spin have proclaimed it one of the most influential independent releases of the past 50 years. Phonography was recorded by a self-taught control-freak, using cheap, malfunctioning analog equipment. Robert Steven Moore was born in 1952, in Nashville. His dad, veteran bassist/producer Bob Moore, taxied between sessions for major stars (including Elvis Presley). But Stevie preferred Brit Invasion, Zappa, Brian Wilson's idiosyncratic arrangements, and outliers like (gasp!) The Shaggs. At the urging of his supportive uncle, Harry Palmer, he moved to New Jersey in 1976.

The Phonography material was recorded by this one-man virtual band at home between 1974 and 1976 with a pair of analog open-reel stereo decks and no multi-tracking equipment. Moore built songs starting with a rhythm track (e.g., played on drums, furniture, or boxes), upon which he layered instrumental and vocal tracks in a primitive sound-on-sound technique. Multiple generations of sound caused frequency loss and sonic distortion - the embodiment of "lo-fi" - but these are charming artifacts that don't obscure the brilliance of the compositions and Moore's masterful music eccentricities. Moore and Palmer culled the top-tier songs, which were interspersed with spoken word, audio verit, and radio snippets to create a "program" effect. The song styles were eclectic, reflecting Stevie's omnivorous music appetite: hard rock, sweet ballads, Britpop, guitar raves, glam, and Zappa-esque weirdness. The album laid the foundation for Moore's four-decade underground career.

R. Stevie Moore has self-released hundreds of albums on each successive era's format du jour (cassette, LP, CD, digital download). He's had vinyl and CD compilations produced worldwide on two dozen indie labels. For a songwriter with a massive catalog of prime material, Moore's revenue stream has barely afforded him the luxury of replacing gear plagued by worn-out switches. Yet most of the surviving labels who turned deaf ears to R. Stevie Moore are now, like him, struggling to make a buck on their catalogs. Their corner-office execs come and go. R. Stevie Moore is still here. And Phonography is back."

1972: CAPT. BEEFHEART & HIS MAGIC BAND -

CAPT. BEEFHEART THE SPOTLIGHT KID

Capt. Beefheart aka Don Vilet was a quirky musician who had his own views on how music should appeal to the average person. He was a unique artists who at times would present musical situations that would leave the listener stunned by what they were hearing. With that in mind, if you are looking to check out any Capt. Beefheart recordings perhaps you should start with this album, Capt. Beefheart The Spotlight Kid.

"On The Spotlight Kid, Captain Beefheart took over full production duties. Rather than returning to the artistic aggro of Trout Mask/Decals days, Spotlight takes things lower and looser, with a lot of typical Beefheart fun crawling around in weird, strange ways. Consider the ominous opening cut "I'm Gonna Booglarize You Baby" -- it isn't just the title and Beefheart's breathy growl, but Rockette Morton's purring bass, Zoot Horn Rollo's snarling guitar, Ed Marimba's brisk fade on the cymbals again and again, and more. The overall atmosphere is definitely relaxed and fun, maybe one step up from a jam. Marimba's vibes and other percussion work -- including, of course, the marimba itself -- stand out quite a bit here as a result, perhaps, brought out from behind the drums and the more straightforward work on Clear Spot. Consider "When It Blows Its Stacks," with its unexpected breaks into more playful parts, or "Alice in Blunderland"'s admittedly more aimless approach, but vibing along well nonetheless. Sometimes things do sound maybe just a little too blasé, but Beefheart at his worst still has something more than most groups at their best. Spotlight does have one stone-cold Beefheart classic -- "Grow Fins," an understated number with fine harmonica and a brilliant lyric about getting so tired of his woman that the best option is to take to the sea and fall in love with a mermaid. Another song, though, does have an all-time great title -- "There Ain't No Santa Claus on the Evenin' Stage." Definite fun touch -- the cover photo of Beefheart looking great in a classic Nudie suit, outlined in yellow light to boot." (allmusic.com)

JOHNNY PIERRE - SPIDER BOY BLUES

LOADING MERCURY WITH A PITCHFORK